From a graduate school student’s lofty dream to a full-fledged citizen science program, eButterfly celebrates its 6th year with a new publication in a special issue of the journal Insects on butterfly conservation. The article – eButterfly: Leveraging Massive Online Citizen Science for Butterfly Conservation – highlights our accomplishments and outlines the bright future of eButterfly.

The power of eButterfly and other massive online citizen science programs lies in the strength and diversity of its participants. Anyone with an interest in butterflies can participate—from the new enthusiast, to the backyard gardener, to the seasoned expert. Since 2012, over 39,000 checklists, representing 230,000 observations and comprising 682 butterfly species, have been submitted to eButterfly by over 5,500 participants. As more participants submit data, an environment of sharing and free data exchange will become the norm between butterfly enthusiasts, scientists, and conservationists.

You might say that eButterfly actually took flight over 60 years ago when Jacques Larivée started Études des Populations d’Oiseaux du Québec bird checklist program. Now with over 10 million records, it’s the longest-running bird checklist program in North America. The daily checklists have provided incredibly reliable information on changes in bird populations, phenology, and geographic and climate abundance patterns at local, regional, and continental scales. His son Max Larrivée grew up checklisting in eastern Québec. It wasn’t birds that caught his eye, but rather butterflies.

“Because of my dad, I swam in butterfly and bird checklists since I was five years old,” said Larrivée. “I first thought of building a checklist-based butterfly website in 2000 when I entered graduate school.”

But it wasn’t until he joined the Canadian Facility for Ecoinformatics Research, led by Jeremy Kerr at the University of Ottawa, that he was able to act on his idea. They wanted to unify all of Canada’s butterfly record data into a single database and continue to survey across the country. And the only way they could do that on a meager budget was to unite a lot of professional lepidopterists and amateur butterfly watchers together.

““In 2010 I pinned two college computer science teams against one another to build a beta version of eButterfly,” said Larrivée. “ And that is how I met Sambo Zhang who turned out to be a real wizard of a programmer for this sort of thing and we’ve been working together ever since.”

After two years of fine-tuning the system, with great support from local butterfly experts Peter Hall, Ross Layberry, Jeff Skevington, Rick Cavasin and the Ottawa area butterfly group, they launched a modest Canadian eButterfly program in 2012. The site was a success in Canada, but they knew they could make it even better if they expand it across the remainder of North America to increase its scope and research potential of the data gathered by the project.

Katy Prudic, a professor at the University of Arizona, was thinking the same thing. “Butterflies, an important part of many ecosystems, are extremely sensitive to changes in temperature, population growth, urban sprawl, land and water use, and many other forces”, Prudic said. “Experts have the ability with powerful computers to interpret these changes and better understand how they are affecting biodiversity – but they don’t have the manpower to gather all the data”. She quickly joined the eButterfly team and helped them expand across North America.

With eButterfly’s popularity rising rapidly, they were poised to evolve the site even further. Kent McFarland, a long-time butterfly watcher and director of the Vermont Butterfly Survey at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, had been managing the first eBird state portal for over a decade. “I started using eButterfly right away when I discovered it and I realized it had the potential to be as big and powerful as eBird one day,” said McFarland.

He joined the team and they all soon traveled to the home of eBird at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology where Team eBird offered to give technical advice for a few days. “The folks at eBird were incredible,” said Larrivée. “They really encouraged us to keep going and were incredibly helpful in advising us on all aspects of this. It really allowed us to leap forward quickly.” Armed with a better understanding of the underpinnings of eBird, the team worked through the fall and winter racing to get the new and improved eButterfly ready by spring.

Like eBird, eButterfly is a source of standardized georeferenced presence/presumed absence data, not just single observation presence-only data. Single observation presence-only data, which includes most citizen science outside of eBird and eButterfly along with data from natural history specimen collections, while valuable is of limited information beyond phenology and broadly defined species distribution for example. These models play a critical role in conservation decision-making and ecological or biogeographical inference, but can lead to suboptimal conservation outcomes. eButterfly data collection protocols offer more and better refined modeling outcomes for conservation and ecology. Building models with suitable data maximizes these rare and valuable resources and delivers outputs that better inform conservation, management decisions and move scientific research forward.

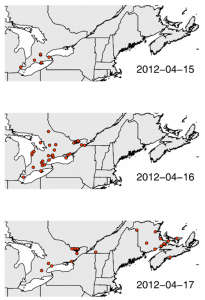

With these growing data, we will be able to address previously difficult ecological and conservation questions. A long-standing challenge in insect conservation has been the difficulty of studying annual cycles for species that undergo broad-scale and complex geographic movements. Massive online citizen science web-platforms have started to make these movements trackable. The migration of the Red Admiral (Vanessa atalanta) during spring 2012 provides an example.

Benefiting from an historically warm winter and spring in their southern United States overwintering grounds, record numbers of Red Admiral butterflies migrated northward following warm southern wind currents in early spring. Observations of Red Admirals were submitted to eButterfly so rapidly and over such a broad area that we could track the leading edge of the migration in real-time across southern Ontario. Using observations captured by participants from 15–17 April, we estimated that the migrant population approached ~300 million individuals migrating over an 800,000 square km area. The estimated migration speed of red admirals closely matched wind speeds recorded in the region during that time period (mean = 26 km/h ± 7 km/h).

Global climate change, land conversion, and human population growth are presenting significant conservation challenges that require understanding processes at continental and global scales. Monitoring systems across full annual cycles in near real-time to identify current and impending threats and to evaluate the outcomes of conservation actions can only be done with continental online, crowd-sourced efforts at multiple spatial and temporal scales. eButterfly is well poised to provide this information.

eButterfly synthesizes large volumes of information in real-time, providing the critical data that is necessary to answer questions about pollinator diversity and distributions and to address potential issues on how anthropogenic and environmental factors affect them. With a continental perspective on insect dynamics, we can better engage policymakers and stakeholders and propose reasonable, understandable, and accountable management solutions. We believe the result of such efforts will be a better understanding of the critical conservation issues facing insect communities across the planet.

To all our users and regional experts, a warm thank you from the butterflies who never cease to amazes us and all the words of appreciation and your continuing support!

Team eButterfly